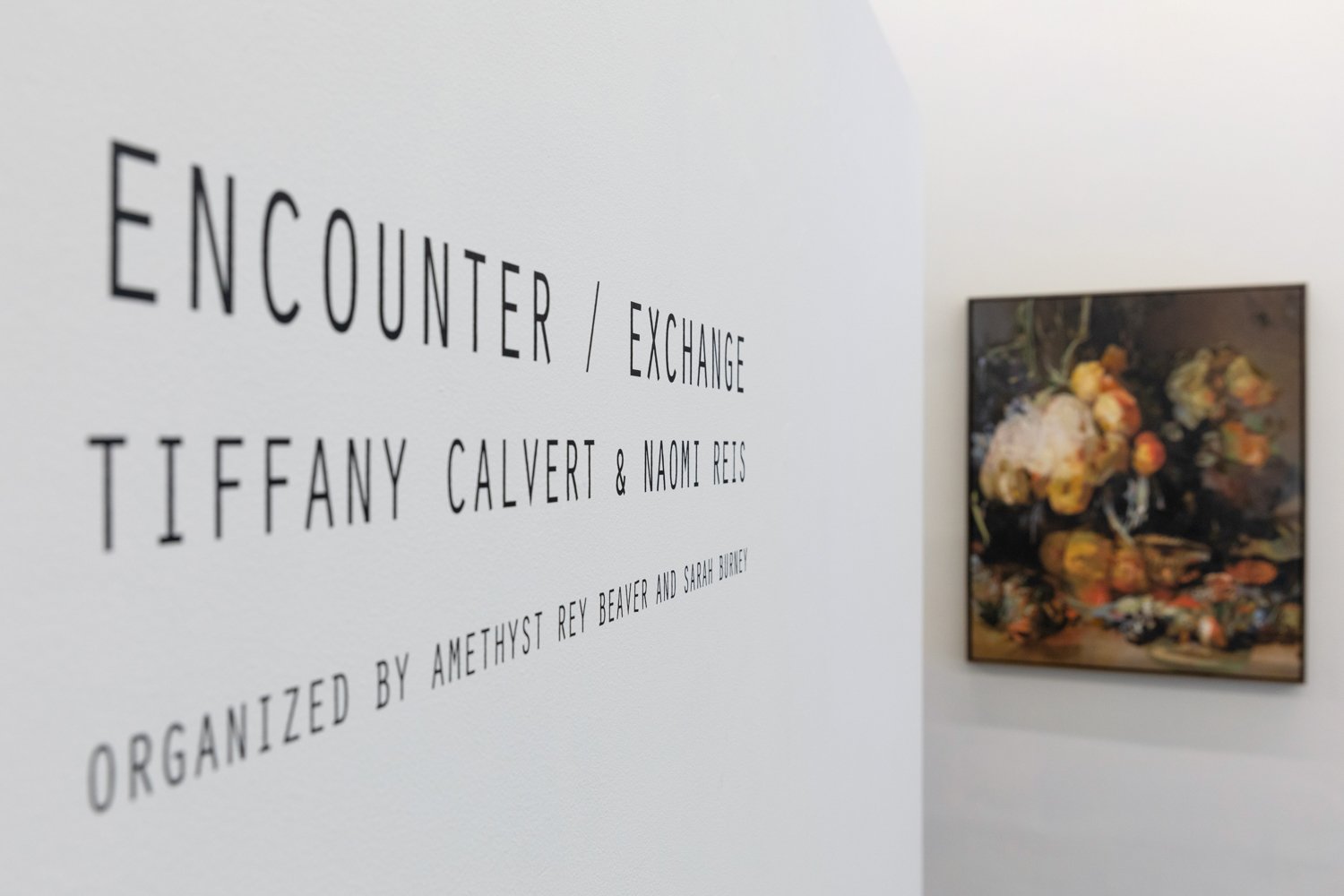

Encounter / Exchange : Tiffany Calvert & Naomi Reis

April 22 - May 26, 2022

At Praise Shadows Art Gallery, MA

Organized by guest curators Amethyst Rey Beaver and Sarah Burney

Click here to view exhibition e-catalogue

Contemporary artists Tiffany Calvert and Naomi Reis leverage technology to re-examine the storied still life genre, approaching the subject through different historic and cultural lenses and incorporating formal and ideological abstraction by machine and their own hand. In doing so, they spark new collisions and intersections for unexpected Encounters and fruitful Exchange.

Tiffany Calvert, #366, 2020, Oil on water based latex print on canvas, 68 x 55 inches. Photo: Sarah Lyon Photography.

Calvert’s paintings begin with an algorithm. She has trained a Style Generative Adversarial Network (StyleGAN) on over one thousand images of historical Dutch still life paintings. Colloquially, she has “taught” a computer to create its own still life painting in the manner of artists from the Dutch Golden Age. The AI-generated images are bewitching art historical deepfakes: extravagant floral arrangements bursting with a kaleidoscope of flowers and leaves and tables laden with lobster, oysters, game and other delicacies. The magnificence of each tableau is heightened by their dark backgrounds and dramatic lighting. Calvert complicates these images with her hand; she masks off large sections of the AI work and paints directly onto the exposed canvas—almost seamlessly matching colors and brushstrokes.

Naomi Reis, 70920 (2:46pm), 2021, Acrylic on washi paper and mylar, 92 ½ x 55 inches. Photo: Takeru Koroda.

In her floral paintings, Reis is also working from digital images—photographs of large floral arrangements that her mother, Setsuko Kawanishi Reis, constructed and displayed outside the family home in Kyoto. The younger Reis uses photo editing software to manipulate the photographs, abstracting the image by extracting tone, flattening color, and altering contrast and saturation. She then recreates the image entirely by hand: cutting out intricate shapes from washi paper that she has hand-painted, meticulously building her subject into a lush paper painting. Her titles refer to meta-data attached to the image (date and time), along with geographic location. Made during the pandemic when international borders were closed, this series bridges the ruptures of distance: geographical, generational, cultural and philosophical.

Naomi Reis, found still life (ivy), 2021, From the Found Still Life series (Kyoto 2015-2020 edition), Acrylic on ink-jet print on washi, 10.25 x 8.25 inches. Photos: Paul Takeuchi.

Reis explores an altogether different kind of still life through her vinyl installation and small works on paper. These works memorialize scenes from walks during her return trips to Kyoto; each image is a found, anonymous, still life arrangement. These moments of paused construction–potted plants soaking in the sun, a hanging tarp–are photographed, digitally simplified, printed onto washi paper and then painted back into, echoing Calvert’s process. Reis centers and highlights her subjects by removing the background and adjacent buildings to isolate the central focus, transforming these found arrangements into anthropomorphic sculptures, a diaristic and unmonumental take on public sculpture. In presenting these works alongside her monumental floral paintings, Reis is encouraging us to look for the beauty and gravitas in these humble, quotidien moments just as we would in the unabashedly glorious and exuberant flowers.

Tiffany Calvert, #391, 2021, Graphite on Rives BFK, 22 x 18 inches framed.

Calvert employs similar redacting techniques in her drawings. Removing the moody background, draped table and lush colors we expect in a still life painting, she centers a cornucopia of food and game on a white sheet. These drawings are studies of construction, of the arrangement of food in Dutch painting, of the display of excess. In these works, like in Reis’s paper paintings, the artist is using her hands to recreate an image she has manipulated digitally.

Each drawing is based on a specific work of art, #391 is from Johann Heinrich Roo’s, Still Life with Dead Poultry, #269 from Jan Weenix’s Still Life of a Dead Hare, Partridges, and Other Birds in a Niche, and #248 is from Jan de Heem’s Fruits and Pieces of Sea. Calvert modifies the images in Photoshop, stripping the background and concentrating the objects closer together, and datamoshing the images to create a glitch-like effect with processing software. She then recreates this composition manually in graphite on paper. The results display both her understanding of Dutch still life composition and her photorealistic draftsmanship.

Johann Heinrich Roos, Still Life With Dead Poultry.

Setsuko Kawanishi Reis’s floral arrangement.

For both artists, a found still life arrangement is the starting point for all the works in the exhibition. Reis’s food still life works, サラダ (salad) and お寿司 (sushi), are based on photographs documenting a rare family meal in Japan with her extended family. Her urban scenes are constructed by unwitting Kyoto neighbors, and her floral works are based on images of constructions built by her mother. Calvert’s drawings are based on specific historic works, and the data-set of still life paintings that she uses to train her software are found and scraped from websites.

Naomi Reis, お寿司†(sushi), 2019, Colored pencil and graphite on paper, 16 x 13 inches framed. Photo: Paul Takeuchi.

In exploring the work of historic Dutch painters and the flower arrangements by Setsuko Kawanishi Reis, Calvert and Reis are continuing dialogues on abstraction. Dutch floral still life paintings, for example, were a depiction of a natural impossibility; all of the flowers in a single vase could almost never bloom at the same time; off-season blooms were grouped for aesthetic and symbolic reasons. The audience of these paintings would recognize the cultural significance of each different flower. Also embedded in each lush arrangement were symbolic references to the cycle of life: tightly closed buds, stunning blooms, drooping petals, and withered flowers. Beautiful, albeit stealthy, these paintings functioned as vanitas, reminders that death and decay come for us all.

Calvert in her studio.

Calvert adds another layer of physical and conceptual abstraction via the stencils (what the artist calls “masks”) that she temporarily adheres to the surface of her AI-generated digital prints before painting. The masks begin as vector drawings in Illustrator: #389 and #365 are freehand drawings—sweeping gestures based on a Braque cubist still life collage—while the masks for the rest of the paintings are based on the DNA sequence of the Tulip Breaking Virus (TBV).

This nod to Cubism is an acknowledgement of another genre that was grappling with the same questions of still life painting as Dutch artists: arrangement, composition and plurality of viewpoints, literal and metaphorical. The artist’s choice to incorporate the DNA sequence for TBV is a decidedly more contemporary commentary. TBV causes a tulip bulb to “break” its lock on a single color, resulting in intricate bars, stripes, and streaks of different colors on the petals. The diseased tulips are striking and led to the “tulip mania” that catapulted the prices of TBV bulbs into unprecedented heights and ultimately destroyed the Dutch economy in the 17th century. The reference to TBV ties into our current lived reality of a global pandemic, and more myopically, to the rapid proliferation of NFTs in the art market, a financial investment that some view as akin to “tulip mania”.

The flower arrangements that inspire Reis’s paintings are an abstraction–or extrapolation–of the centuries-old Japanese art form of ikebana. Like Dutch still life painting, ikebana uses flora for its beauty and symbolic references to mortality and the cycles of life. Setsuko Kawanishi Reis started making ikebana arrangements in her late 60s and continued the practice throughout the time she took care of her ailing husband. Ikebana’s reverence and celebration of the natural world and goal of capturing the essence of each season through flowers, leaves, stems, and branches, resonated deeply with her. But where ikebana prizes a minimalist purity attained by strict adherence to rules regarding form and composition, Setsuko Kawanishi Reis jettisoned the strict rules and embraced a heady maximalism. Her arrangements are larger than life, housed in a non-traditional vessel, a gifted tea urn, and proudly displayed outside of her home. Reis, the younger, is celebrating her mother’s late found creativity and rebellion.

Calvert and Reis both welcome the machine as a collaborator in their work, for the software in each is responding to the constraints of the situation–creating new images from a rather limited dataset, and compressing and degrading a photograph to be sent more efficiently–thus making their own creative contributions. Anomalies in Calvert’s original dataset of historic paintings–hanging hares, pheasant feathers, etcetera–are tricky for the computer to visually define. To an algorithm, the shapes and hues of oysters, melons, and ranunculus flowers look the same and the new images created by the program are highly detailed abstractions of organic shapes that, while visually linked to their predecessors, are also intricate, bizarre, and otherworldly. This is perhaps most evident in Latent Space Walk #1, a looping animation of all the generated output images from a dataset of over a thousand historical still life works. Viewed collectively, the familiar yet uncanny images bleed together revealing the patterns and gaps in the machine’s understanding of these complex paintings and the creative liberties it takes when producing its own.

Tiffany Calvert, Latent Space Walk #1 (stills), 2020, Animation generated by artificial intelligence software of all generated output images from a dataset of 1,007 historical still life images.

Calvert’s final interventions in her paintings adds another layer of abstraction: brushstrokes. Working quickly with oil paint and matching the colors of the base AI image, her sumptuous, sculpted swirls of oil paint disrupt the smooth surface of the digital print: the intentional, human glitch.

Tiffany Calvert, #371 (detail), 2021, Oil on water based latex print on canvas, 50 x 39.5 inches. Photo: Sarah Lyon Photography.

Where Calvert’s glitch and datamoshing is additive, Reis plays with the moments where information is lost: the deterioration of a digital image. The photographs taken by her and her mother lose resolution as they are shared and saved, as the instruments of communication compress the image in order to transfer it. She embraces this digital breakdown, exaggerating the loss of image quality by converting them to vector files, a translation that flattens tonal gradations in the image. She then applies an intuitive succession of filters and effects to the image until the photo has been converted into a pixelated and increasingly abstract image.

Naomi Reis, 111119 (90˚E) + 71220 (10:17pm) (in progress), 2022, Acrylic on washi paper and mylar, 24 x 20 inches framed.

Reis’s final translation, recreating her digital image into a physical painting, pushes the pixelated aesthetic further. More information is lost as she paints sheets of washi paper, cuts out shapes by hand and painstakingly rebuilds the arrangement. Her choice of material and process is significant. She is drawn to fiber-based Asian paper for its strength, ubiquity and historical importance in Japanese culture. The time-consuming and labor-intensive processes her paper paintings demand becomes a devotional act. In dedicating such time to meditate on her mother’s creation and revel in the sheer beauty of flowers, Reis is pushing back against an art history that dismisses art forms historically practiced by women and that center “beautiful" subject matter, as amateurish or non-serious art. She is giving power to the feminine and the decorative, punching it up and allowing it to take up space and time to be exuberant and wild.

Naomi Reis, 111119 (90˚W), 2021, Acrylic on washi paper and mylar, 49 ¼ x 36 ⅞ inches framed. Photo: Paul Takeuchi.

Beautiful, lush, still life paintings, especially those of flowers, fruit and other foods are a loaded subject matter for any contemporary woman-identifying artist. Historically dismissed as frivolous and decorative, these subjects were in fact often the only subject matter that were considered appropriate for women to paint. This, coupled with the long, tired history of analogies between flowers and femininity—symbolic and physical—make Calvert and Reis’s reclamation of these artistic muses a daring choice. Their works are not strictly feminine, delicate, or fleeting; rather, they belie other, introspective, darker, disguised meanings that beckon viewers to look closer and think more deeply. The artists reevaluate still life paintings, deconstructing the rigid hierarchies imposed on the genre, incorporating new technologies, introducing randomness, embracing the glitch, and revealing the complexities and idiosyncrasies of subjects traditionally passed over as simply beautiful.

Tiffany Calvert, #367, 2020, Oil on water based latex print on canvas, 68 x 55 inches. Photo: Sarah Lyon Photography.

Installation images by Dan Watkins. All other images courtesy of the artist unless otherwise noted.